Do Children Make You Happy?

It depends on what you measure

Back in grad school, I remember hanging out in Chapel Hill with my friend Craig Foster, trying to come up with a clever new meta-analysis to do. We were intrigued by Roy Baumeister’s classic book Meanings of Life and his discussion of the apparent negative effect of children on marital satisfaction.

This finding presented a bit of a paradox. On one hand, sociologists and psychologists were arguing back in the 1950s that raising children wasn’t always easy. The arrival of the first child was described as a kind of “crisis” for the couple. This was essentially a stress model of parenthood: children introduce sleep deprivation, time scarcity, role overload, diminished couple-time, and new domains for conflict—money, chores, parenting style, in-laws, and the basic division of labor. Basically, raising kids is tough and puts stress on the marriage. On the other hand, in the 90s when we were having this discussion, getting married and having children was still the “normal” and desirable track. So we (perhaps naively) thought it plausible that parenthood would be associated with higher marital satisfaction.

Craig and I started our meta-analysis, and eventually invited our smart friend Jean Twenge on board to actually get it finished. The basic finding was pretty consistent with the stress idea. On average, parenthood was associated with lower marital satisfaction. The effect size was small, on the order of a couple tenths of a standard deviation depending on the comparison—it was not automatic Divorce Court—but it was enough to be interesting.

But this drop in marital satisfaction was not uniform. The negative association was most pronounced for parents of infants and young children, especially mothers. And this makes sense. Human infants are neurologically immature compared to most mammals, so parenting human infants is very hard work. And, on average, a disproportionate share of the early parenting is done by the mother (mothers still do a lot of parenting later, but the overall amount drops, especially in terms of caregiving).

But parenthood is complicated. It is difficult, but it also gives you a purpose.

Sonja Lyubomirsky and colleagues dug into this question by looking at parenthood and personal happiness, and also separated pleasure from meaning. Parenting may not maximize fun or hedonic enjoyment, especially in the infant years, but it may add meaning, purpose, and a sense of significance. There are some complexities to these findings that I am brushing over—but if you only measure the fun part of happiness, you miss what many parents are actually optimizing.

And to make it a little more complicated, there are a couple of ways that you can answer the question about kids and happiness or marital satisfaction. You can compare couples with and without children like we did in our meta-analysis, or you can follow couples across time and see what happens to their happiness when they have kids.

In some of these longitudinal panel studies, the pattern looks like this: a rise in happiness or life satisfaction leading up to a first birth (an anticipation bump), a peak around the birth, and then a decline afterward back toward pre-birth levels. And the average hides variation: for some parents the post-birth period is a genuine drop; for others it is stable; for others it is positive.

So, our story so far is that children might provide a happiness bump before the first birth; might add stress to the marriage after they are born, especially for moms with infants; and might add meaning in life for parents over time, but perhaps at the cost of some happiness or “fun.”

But I also think this story could be changing. In the last century, people just got married and had kids. It was the path, especially in the postwar period. Obviously, this is no longer the case. Marriage and children are becoming more scarce and sometimes start to feel like a luxury good for many people. This isn’t a new idea—people were writing about this a century ago after the Great War—but the relatively high cost of raising children, especially housing and education, versus the collapsing cost of entertainment and distraction, means lots of people will choose not to have children. And it would make sense that the married couples who do have children really want them.

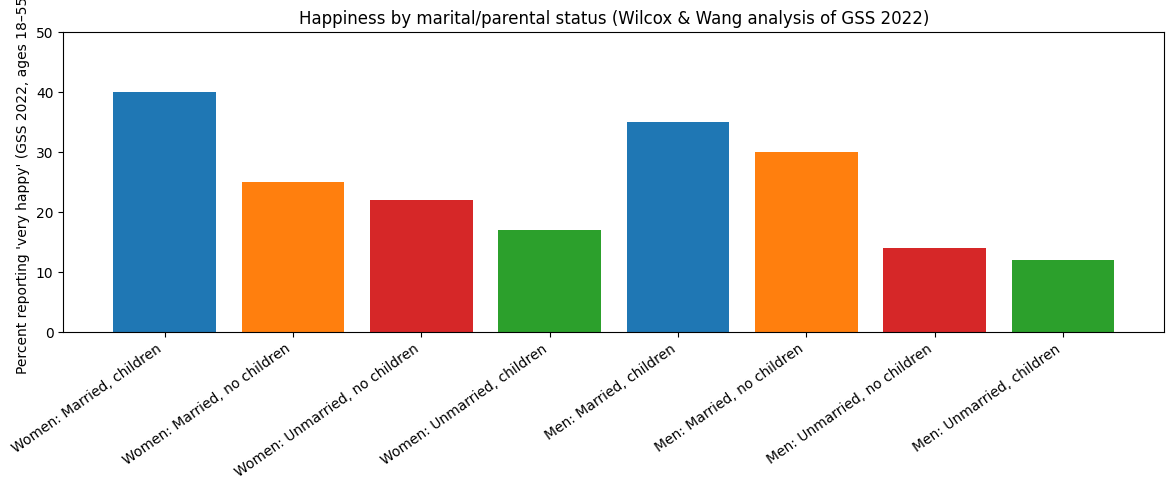

And this brings me to recent national surveys. Brad Wilcox’s cross-sectional work with Wendy Wang, using the General Social Survey, reinforces the idea that the overall story is not simply “parents are unhappy.” It now looks like married people who have children are the most likely to report being “very happy”—and unmarried people with children often the least likely.

This new research puts a slightly different frame on the early work. Children can be challenging for a marriage in ways that show up as modest dips in marital satisfaction, especially for mothers of infants, while still being associated—on average—with higher global well-being and a deeper sense of meaning. So I do not think children are best thought of as a “crisis” for marriage. Instead, raising a child today seems like a difficult challenge that comes with obvious costs but also incredible rewards.

Links to my work: Homepage; Peterson Academy; Books on Amazon

My New Peterson Academy course: The Psychology of Wealth

My PA Intro to Psych history lecture now on YouTube

My latest podcast interview on Orthodoxy: Link

Some citations

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Foster, C. A. (2003). Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(3), 574–583. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00574.x

Baumeister, R. F. (Ed.). (1991). Meanings of life. Guilford Press.

Aassve, A., Goisis, A., & Sironi, M. (2012). Happiness and childbearing across Europe. Social Indicators Research, 108(1), 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9866-x

Negraia, D. V., Augustine, J. M., & Prickett, K. C. (2018). Gender disparities in parenting time across activities, child ages, and educational groups. Journal of Family Issues, 39(11), 3006-3028.

Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., English, T., Dunn, E. W., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). In defense of parenthood: Children are associated with more joy than misery. Psychological Science, 24(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612447798

Dyer, E. D. (1963). Parenthood as crisis: A re-study. Marriage and Family Living, 25(2), 196–201. https://doi.org/10.2307/349182

LeMasters, E. E. (1957). Parenthood as crisis. Marriage and Family Living, 19, 352–355. https://doi.org/10.2307/347802

Myrskylä, M., & Margolis, R. (2014). Happiness: Before and after the kids. Demography, 51(5), 1843–1866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0321-x

Spitzer, S., Greulich, A., & Hammer, B. (2022). The subjective cost of young children: A European comparison. Social Indicators Research, 163(3), 1165-1189.

Loo, J. (2023). Marriage rate in the U.S.: Geographic variation, 2022. Family Profiles, FP-23-23. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research.

Martin, E. S. (1922). The Luxury of Children & Some Other Luxuries. Harper & brothers.

Wilcox, W. B., & Wang, W. (2023, September 12). Who is happiest? Married mothers and fathers, per the latest General Social Survey. Institute for Family Studies.

Excellent as always. I think meaning gets a bad wrap in comparison to happiness. Happiness is fleeting. Shifts with the slightest external stimuli. Meaning perseveres.